Given a scale from 1 to 10, where 1 is the lowest point and 10 is the highest, how do you rate yourself as a writer? I recently asked this question of a group of doctoral students. What do you suppose their answers were? How would you answer that question? Predictably, their ratings ranged from 3 to 6, with several explaining that writing has always been a struggle and a few sharing that they thought they were decent writers until they began grad school. It is noteworthy that no one, including the faculty members in the room, rated themselves a 10. All of us considered academic writing as something we are still trying to master. I shared that as a graduate student I too would have likely rated myself on the low end of the scale and that it has been a long journey to developing a productive relationship with the process of writing academic papers.

It is perhaps unsurprising that many of us, especially those who chose to study mathematics or science, would have such doubts about our own writing ability. What is perhaps more surprising is that even successful writers do not think of themselves as good writers. Many writers are quoted as saying things such as this: “Writers do not like to write; they like to have written.” If even accomplished authors doubt their writing skills and most people categorize themselves as not very good writers, then it is important to consider the ways in which we read and provide feedback to manuscript authors.

In a previous editorial (September 2013), Peg Smith called attention to the fact that writing for publication is largely a process of revising and resubmitting manuscripts, and that a natural part of submitting a manuscript to the Mathematics Teacher Educator (and other journals too) is to have it undergo at least one round of revision. Because receiving feedback to rewrite large portions of a manuscript can be equally as unsettling as releasing the manuscript for review, reading useful and educative feedback that will support this process is extremely important. In reflecting on why MTE has made a commitment to giving educative feedback to manuscript authors, former MTE Panel Chair Denise Spangler shared the following:

In my first editorial (September 2015), I highlighted MTE’s longstanding commitment to providing educative feedback to authors of all manuscripts, not just to those whose manuscripts will end up published in the journal. In this current editorial, I delve a little bit deeper into how this journal approaches manuscript reviews. First, I share some conceptual tools to help clarify the notion of educative reviews and how this approach matters for MTE and, more broadly, to our field.

Peter Elbow, a writing and rhetoric scholar, has published many articles and books about the reading/writing dialectic and the problems created by the dominance of reading over writing in K–12 schooling. He argues that the early and ongoing emphasis on consuming rather than producing text is partially to blame for the challenges that many of us experience with the writing process. These challenges are carried into graduate school and continue to the authoring of manuscripts for professional journals. Elbow (2000) explains that the teaching of reading tends to privilege skepticism and critical reading skills and that this approach places the reader in an adversarial role to that of the author. Elbow calls this approach the doubting game; that is, the reader searches for flaws in the writer’s argument and for what has been omitted or neglected. This approach to reading often results in readers’ feedback that is evaluative of the authors’ argument and provides no help to writers as to how to go about revising and improving their writing skills.

In preparation for writing this editorial, I asked an MSU colleague whom I consider to be a great writer to share the worst feedback that she had ever received. It took her all of two seconds to produce the following: “The paper is well-written and well organized, as it should be, but the author has nothing to say.” My colleague also shared that it took her a while to recover from this terrible feedback and get the energy to eventually revise the paper and send it out again for publication. The best revenge, she says, is that this piece is now published in a top peer reviewed journal. This is a prime example of a reviewer adopting a doubting approach to reading manuscripts. Elbow (2000) also suggests that how that feedback is communicated matters, because as noted earlier self-doubt is a common challenge for all writers.

I am sure each of us can produce similar stories of unsettling feedback from reviewers. I have too many to share in a single editorial, so I have chosen one that took me a while to recover from and is still a vivid memory. In one of my master’s thesis chapters, my adviser wrote: “Did you write this?” Upon reading this I was at first relieved that there was nothing in that chapter that needed to be revised, unlike the rest of the document, which was filled with comments. But this sudden relief did not last long as it dawned on me that this note was no compliment on my writing skills. This piece of feedback was more hurtful than useful and it raised all sorts of questions for me: Was the note suggesting that I had plagiarized the text, or that someone else wrote that chapter for me? Was it implying that I could not possibly write this well? What exactly was this feedback intended to communicate and how was it supposed to help me improve my academic writing skills? This is one of those terrible feedback stories that eventually sent me on a trajectory of learning more about writing and approaches to providing useful and helpful feedback to authors of academic papers.

Using Elbow’s (2000) framing about reading and giving feedback to authors, we could say that both examples of feedback I described above are from readers who used the doubting approach to reading text. Below are more examples of evaluative comments that are not appropriate to provide to authors. Notice that a common feature across this list is that the comment renders a categorical evaluation on the paper or the author, without providing the writer a clear pathway for revising or advice for improving his or her writing skills.

• The author fails to provide appropriate evidence.

• This paper is not revisable!

• There is nothing new or original about this study.

• The author is obviously not a native speaker—there are many grammar issues that need to be fixed.

• I am not convinced that your study shows the kind of impact that you argue that it makes.

As an alternative to the doubting game Elbow (2000) proposes the believing game as a different approach to reading and providing feedback to authors. This entails acting as if one believes everything the author claims and to identify ways to strengthen those claims by explicitly pointing out where and how those could be improved. Contrast the above evaluative statements with feedback that I received from Kristen Bieda, MTE associate editor, and Laura Van Zoest, chair of MTE’s Editorial Panel, on a draft of my first editorial and that embody Elbow’s believing stance to reviewing manuscripts.

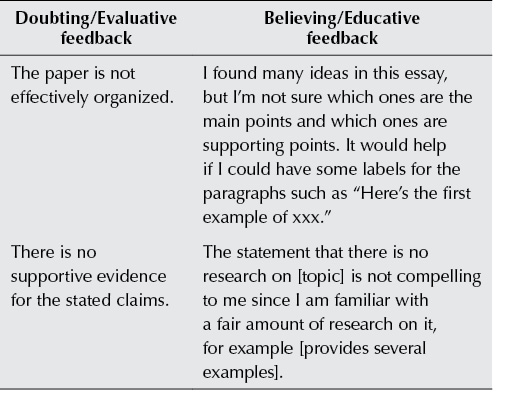

I feel very privileged and spoiled to have access to this kind of educative feedback to my writing! This is the kind of feedback that all writers deserve and that MTE is committed to and is working to provide to manuscript authors. Note that these are not simply feel-good comments to inflate a writers’ ego or provide false praise. Educative feedback challenges the writer while it also supports her to improve her arguments and writing skills. In our case we use MTE’s criteria for publication to guide the reading and the construction of feedback to manuscript authors. Here are a few contrasting examples of doubting/evaluative and believing/educative reviewers’ comments.

All four manuscripts in this issue benefited from the generous and educative feedback reviewers provided to the authors and editors. A noteworthy thematic connection across all four manuscripts and this editorial is their focus on the importance of attending to the impact of evaluative and insensitive language, especially toward teachers and students of mathematics. Overall this issue of MTE invites us to learn more about the important benefits of adopting an educative stance across the many contexts of teacher education, including writing for publication.

In the article “(Toward) Developing a Common Language for Describing Instructional Practices of Responding: A Teacher-Generated Framework,” Amanda Milewski and Sharon Strickland share an analytical framework generated by secondary mathematics teachers for tracking changes to their own responding practices across time. They argue for this type of collaborative work with teachers as a means to develop common language for instructional practice that empowers both practitioners and researchers of mathematics education.

In “Inviting Prospective Teachers to Share Rough Draft Mathematical Thinking,” Eva Thanheiser and Amanda Jansen share a novel approach to supporting prospective elementary teachers’ public sharing of their mathematical ideas by using a simple and purposefully designed intervention. They provided a labeling system for prospective teachers to indicate the level of completeness and correctness of their thinking before publicly sharing their work in a mathematics content course for teachers. The authors share how this intervention made important contributions to the prospective teachers’ thinking and to the nature of their class discussions.

In “Preparing Preservice Teachers for Diverse Mathematics Classrooms Through a Cultural Awareness Unit,” Dorothy White and colleagues share a cultural awareness unit they designed to support beginning conversations with prospective teachers about culture, equity, and diversity in the mathematics classroom. They discuss the expected and unexpected challenges and impact of this unit on the prospective teachers and the mathematics teacher educators. They also share their advice for revising and improving this unit and considerations for using it in other institutional and geographical contexts.

In the invited piece, “Supporting Teacher Noticing of Students’ Mathematical Strengths,” Lisa Jilk describes a teacher video club focused on identifying and naming students’ mathematical strengths rather than their deficits. She illustrates important shifts in teachers’ ways of talking about students’ mathematical activity and shares the facilitation tools that supported their shifts toward noticing and talking about students’ mathematical potential.

These are important articles that have much to contribute to the knowledge base and the practices of mathematics teacher educators. I invite you to connect with and build on what these authors have shared about their work. You could try reading them using Elbow’s (2000) doubting and believing approaches to reading text so as to extend your understanding of these two approaches. I also invite you to try the believing/educative approach to reading and providing feedback to manuscript authors next time you review an MTE manuscript. This approach to reviewing journal manuscripts is consistent with COPE’s (2013) “Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers.” Here I share just a few of those guidelines to further corroborate the importance of providing educative feedback to manuscript authors.

Peer reviewers should do the following:

• Be objective and constructive in their reviews and provide feedback that will help the authors to improve their manuscript.

• Avoid making derogatory personal comments or unfounded accusations.

• Be specific in their criticisms, and provide evidence with appropriate references to substantiate general statements such as, “This work has been done before” to help editors in their evaluation and decision and in fairness to the authors.

• Remember it is the authors’ paper; avoid the temptation to rewrite it to their own preferred style if it is basically sound and clear. Suggestions for changes that improve clarity are, however, important.

• Be aware of the sensitivities surrounding language issues that are due to the authors writing in a language that is not their own, and phrase the feedback appropriately and with due respect.

• Make clear which suggested additional investigations are essential to support claims made in the manuscript under consideration and which will just strengthen or extend the work.

See the complete listing at COPE, 2013.

Reviewing journal manuscript submissions is serious work that deserves recognition. I especially thank all of the MTE Editorial Panel members (Laura Van Zoest, panel chair; Nadine Bezuk, Christine Browning, Rebekah Elliott, Anthony Fernandes, Randall Groth, Amy Hillen, Jeff Shih, and David Barnes) for their dedication and consistently thoughtful feedback to authors. I also thank all the MTE reviewers in our database who are actively reviewing manuscripts. In the recent editorial board meeting, we reported that 284 reviewers were involved in the peer review process this past year. Among them the following reviewers deserve special recognition for providing consistently outstanding peer review feedback to authors: Julie Amador, Angela Barlow, Tonya Bartell, Corey Drake, Keith Leatham, Michael Steele, and Eva Thanheiser. We hope to continue to expand this list of outstanding reviewers in the years to come.

This year MTE is focusing on developing reviewers’ capacity to provide educative feedback to prospective authors. At the 2016 AMTE and NCTM annual meetings the MTE journal sessions will focus on developing reviewers’ capacity to provide educative feedback to authors. These types of sessions are important to improve the quality of manuscripts and the reviewers’ capacity for providing educative reviews, and to demystifying the process of writing for publication. This is indeed going to be another exciting year for the Mathematics Teacher Educator and its mission of building a professional knowledge base for mathematics teacher educators that stems from, develops, and strengthens practitioner knowledge.

References COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics). (2013). Ethical guidelines for peer reviewers. Retrieved from http://publicationethics.org/files/Peer%20review%20guidelines_0.pdf

Crespo, S. (2015). “Who wants to be an MTE editor? A goal for your professional bucket list.” Mathematics Teacher Educator 4(1): 3–5.

Elbow, P. (2000). Everyone can write: Essays toward a hopeful theory of writing and teaching writing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Smith, P. (2013). “Editorial: Revise and resubmit: It’s not a consolation prize!” Mathematics Teacher Educator 2(1): 3–5.

Author

Sandra Crespo, Department of Teacher Education, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824; [email protected]