November 2019

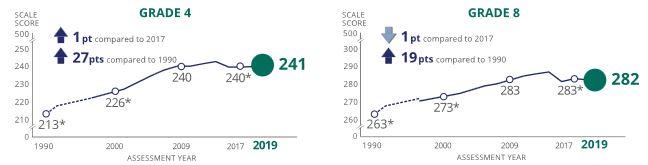

Since 1990, the average mathematics score on the Nation’s Report Card has gone up 27 points in grade 4 and 19 points in grade 8. However, the trend has been relatively flat since 2009. In the 2019 report, released by the National Assessment Governing Board on October 30, the average mathematics score in 2019 is 1 point higher in grade 4 and is 1 point lower in grade 8 than in 2009.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

Over the past 50 years, the Nation's Report Card, also known as National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), has informed the public about students’ performance in mathematics in grades 4, 8, and 12.

The assessment also collects information from teachers. According to the report, 21 percent of teachers who taught fourth grade reported that a lack of adequate instructional materials and supplies was a moderate or serious problem in their schools. Of teachers who taught eighth grade, 19 percent reported that a lack of adequate instructional materials and supplies was a moderate or serious problem.

Although the NAEP results are a cause for concern, I argue that we must view these results in the context of reforms over the past 30 years. What impact have reforms during this period had on mathematics teaching and learning? The significant gains on NAEP were made during a period when specific funding was provided by the Dwight D. Eisenhower Mathematics and Science Education Act. This national policy and funding supported professional development for teachers to build content knowledge and to improve teaching practices. During this period, Eisenhower funds supported teachers in a wide range of professional development activities, including their attendance at professional meetings to connect with other professionals.

Eisenhower funds played a significant role in my own development as a teacher. Eisenhower funding supported my first professional meeting as a teacher. I attended an NCTM Regional Conference in Philadelphia, which exposed me to teaching practices that made me think of the connections between problem solving and discourse. I built professional links to mathematics educators who pushed me to make shifts in my teaching practices. Simply put, that meeting changed me as a teacher of mathematics. I moved from being teacher-centered to centering my teaching on my students’ thinking and understanding. I believe engagement in professional meetings can be transformative for many teachers and that investments in teachers’ professional learning and development are part of a broad process for improvement in mathematics teaching and learning.

I wonder whether the shift from the supports provided by the Eisenhower funds to the 2002 Elementary and Secondary Education Act, better known as the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB), had an impact on NAEP scores. The NCLB law brought educational reform with the premise that setting high standards and establishing measurable goals will improve student achievement and change American school culture. NCLB required states to implement student testing, collect and disseminate subgroup results, ensure teachers are highly qualified and guarantee that all students achieve academic proficiency by 2014. States were required to use sanctions to hold schools and districts accountable for their success in meeting adequate yearly progress (AYP) goals set by states, for both overall performance and performance in each subgroup.

I argue that the policy change from Eisenhower funding to NCLB and its sanctions had an impact on mathematics teaching, which resulted in the stagnation we see on NAEP results over the past 10 years. NCLB assumed that solutions to issues of student achievement required increased accountability with a focus on metrics of inputs (content exposure) and outputs (assessing acquisition of content). For many students, such a solution reduced instructional strategies to focus on the acquisition of rote knowledge covered on standardized tests and dissociation from higher levels of mathematics content and practices supportive of critical thinking, problem solving, and mathematical reasoning. Student learning is much more complex than metrics focused on inputs and outputs.

I am not arguing for moving away from metrics of inputs and outputs. We learn a lot about achievement, content exposure, and access to human and material resources by collecting and disseminating results across multiple groups. Policies focusing only on inputs and outputs ignore the realities of students’ and teachers’ lives. When we focus on the realities and needs of teachers and learners, we see the nuances of contexts, cultural understandings, backgrounds, and identities for teaching and learning. Too often, focusing only on metrics ignores these nuances.

I believe, as educators, we must become more involved in the policy space. NCTM will continue to advocate for policies that invest in teachers and students. These investments should include, but are not limited to, supports for teacher professional development and expanded opportunities for students to engage in and learn mathematics.

I invite you to share your thoughts, wonderings, and ideas with me on MyNCTM or Twitter.

Robert Q. Berry III

NCTM President

@robertqberry