By Harold Reiter, posted January 30, 2017 —

With

wooden cubes as manipulatives, I create problems related to pattern

recognition, spatial visualization, polynomials, fractions, probability,

and pretty combinations of these ideas. Today’s problems are about

probability:

Build a 2 × 2 × 2

cube using eight unit cubes. Then imagine

painting all six faces of the large cube. Cut the painted cube apart and

randomly select one of the eight unit cubes, which you then roll like a

die. What is the probability that a painted side comes up?

Most students

will quickly reply with the answer of one-half. Then I can ask, “Where do

we go from here?”

When I urge them to try the

1 × 1 × 1 cube

1 × 1 cube, they laugh and answer that the

probability is 1. I ask, “What about the 3 × 3 × 3 cube?”

Some students realize that

when the

3 × 3 × 3 cube is painted, four types of unit cubes

are produced:

• 1 with

no painted sides

• 6 (we’ll

call face cubes) with one side painted

• 12 edge

cubes with two painted sides

• 8 corner

cubes with three painted sides

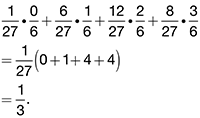

This

cube classification leads to the probability

For the cubes with volumes 1, 8, and 27, we find the probabilities

1, 1/2, and 1/3. This might not be a coincidence. What’s next?

Some students will dive right into the

4 × 4 × 4 case. Others

will begin to ponder a method easier than cube classification.

Every one of the 27

• 6 = 162 sides is equally likely to be selected,

but only 54 sides are painted, because each of the six faces has area 9. Now (9

•

6)/(27 • 6) = 1/3, and

we can see pretty quickly that in the general case of n ×

n × n cubes,

we get (6n2)/(6n3) = 1/n as the probability that a randomly selected face is painted.

From here, we talk about rectangular boxes. Build an

a

× b × c block of cubes, with a < b < c.

We can ask the same question, or we can turn it around. Suppose the

block is painted on all six of its faces, and once again a unit cube is

randomly selected: Find all triplets (a, b, c) that would yield the probability 2/7 that a

painted face comes up.

Some students will see right away that

a = b = c is impossible

because 2/7

is not a unit fraction. (What should I tell my little fourth-grade friend

Lucio, who tells me that a 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 cube will work? He actually built such a

cube from cardboard at home!)

Giving students time to experiment and think is

important at this stage. Learning to tolerate confusion keeps them from saying, “But wait, you haven’t taught us how to do

that kind of problem.” After students understand that all the sides are equally

likely, they do not need to focus on the individual cubes. So, the number of

sides of all the cubes is 6abc, and

the number of painted sides is 2(ab + bc + ac).

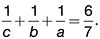

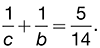

Setting this fraction equal to 2/7 and simplifying the equation results in

But a = 1 makes the left side too big, and a = 3 makes the

left side too small (unless a = b = c

= 3, which doesn’t work). With a =

2, we can subtract 1/2 from both sides to yield

This has the unique integer solution {b = 3, c = 42}.

(Ed

note: For more investigation of the Painted Cube problem and probability,

take a look at the Activities for Students department article “What’s in a Cube”

in the upcoming March 2017 issue of MT.)

Harold Reiter has

taught mathematics for more than fifty-two years. In recent years, he has

enjoyed teaching at summer camps, including Epsilon, MathPath, and MathZoom.

His favorite current activity is teaching fourth and fifth graders two days

each week.