By Glenn Waddell Jr., posted April 10, 2017 —

The

game of Set is a go-to game among my math friends. Whenever we get together for

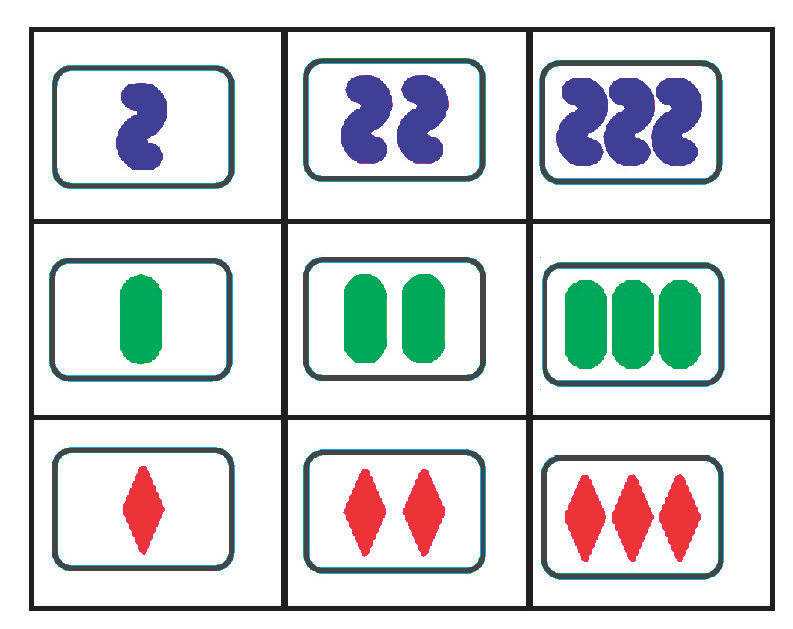

a game night or barbeque, someone invariably pulls out Set. The game consists

of eighty-one cards marked with one, two, or three symbols that vary in color, shape,

and shading (see pictures on the game’s homepage). Each of the deck’s eighty-one cards

contains symbols with four features:

-

color (red, purple, or green);

- shape (oval, squiggle, or diamond);

- number (1, 2, or 3); and

- shading (solid, striped, or outlined).

The

goal of the game is to find a “set” of three cards on which the symbols

individually match exactly or are all different. A set could have, for example,

three cards with symbols that are all green, all solid, and all squiggle shapes,

but each card has a different number of squiggles.

Play

begins with an initial group of twelve cards laid out on the table. Set is a

game of speed in which you have to act faster than your opponents to capture a set.

The game has some interesting and

complex mathematics. Quanta Magazine

published an article in

2016 about an extension generalizing the game to n dimensions.

My

question is different: What happens if we associate geometric meanings with the

definition of a “set”? For example, we could redefine a set to be a “line.” That

is, in the game of Set, a “line” consists of exactly three cards. Then, what

does a particular set represent, and how would we represent a plane using this

definition?

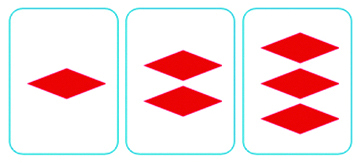

What

does it mean for two sets to be parallel? We could say, for example, the sets above

(solid red diamonds and solid green ovals) share no card in common, and

therefore do not intersect. However both sets are in the plane of “solids” because

all the symbols are solid.

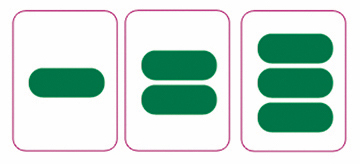

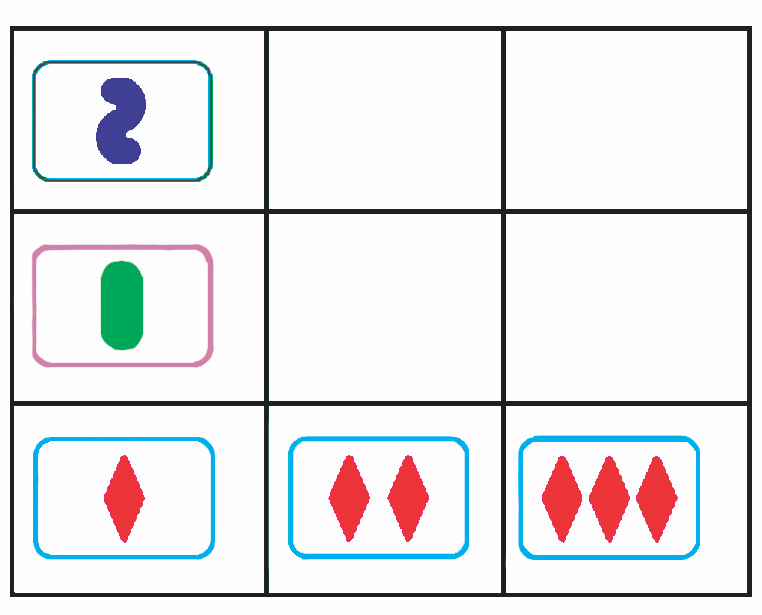

What

would it look like for a pair of sets to intersect? This pair of sets shares

the single solid red diamond and so meets the condition of intersecting once.

But additional sets also in this plane of solids can be created to intersect and

share only one card of the original set. In fact, exactly eight sets can be

made! (Complete the grid with solid purple squiggles in the top row and solid

green ovals in the middle row.)

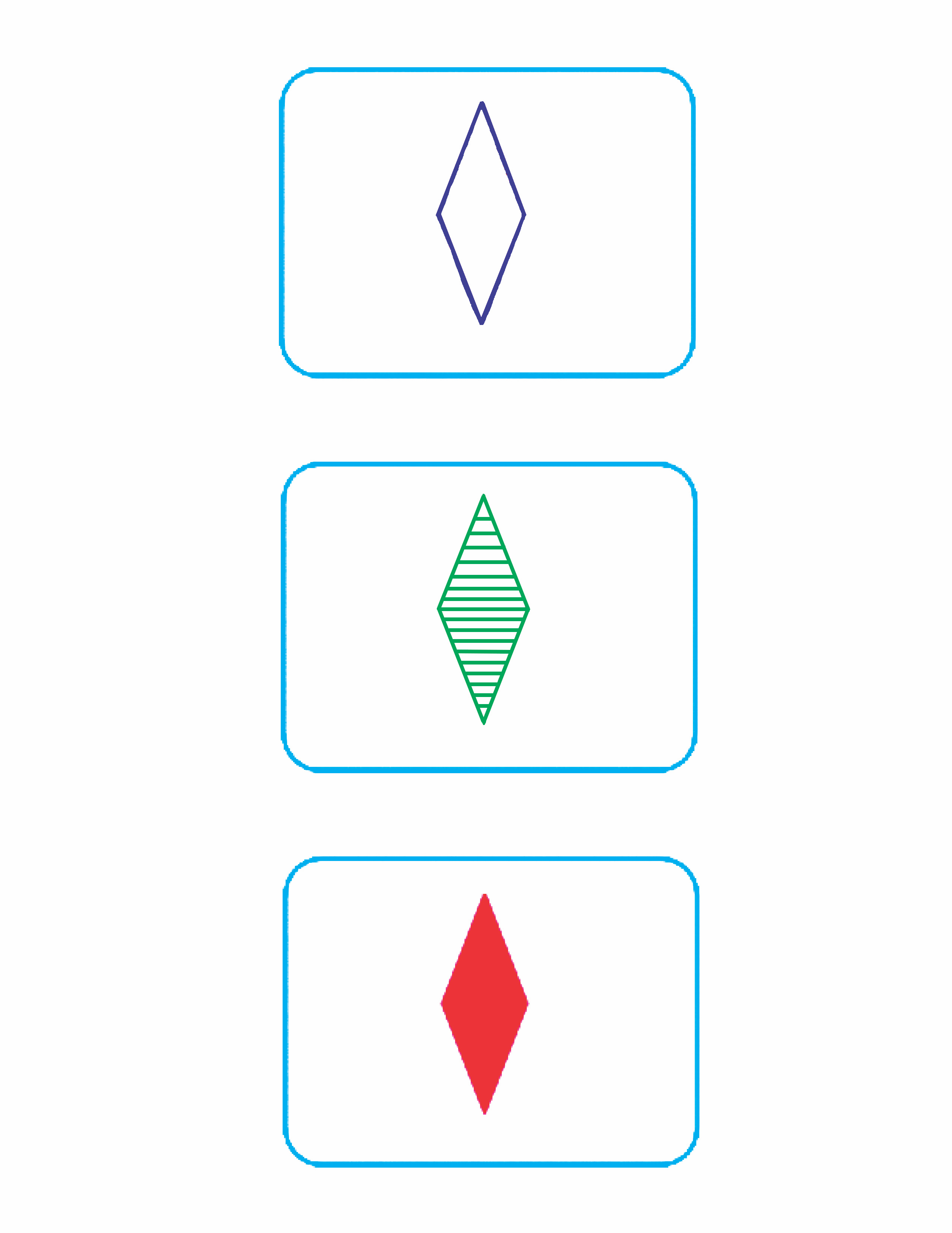

This

outcome—that eight lines can be in a plane and intersect only one time—is impossible

in Euclidian geometry. It is even more thought-provoking to imagine the plane

of solids laid out on a table with two sheets of glass above them. An empty

purple diamond and a shaded green diamond arranged vertically above the single solid

red diamond would create a set that intersects the solid plane only once as

well.

This

set of single diamonds forms one edge of a cube; each side of the cube is a

plane that contains eight different sets that each intersect only one time. Or

at least that is my guess. I haven’t actually built that cube. But this cube

must have twenty-seven cards, resulting in fifty-four leftover cards.

Will

those fifty-four cards also create their own two cubes of sets? Will the second

cube be composed of intersecting sets and the final cube be non-intersecting?

This

activity brings to mind several questions that all lead to set theory and

combinatorics. I am in awe that a fun way to spend a summer afternoon with

friends can lead to such complex constructions and deep mathematics. This is

why I find such joy in mathematics. That it is an extension of the essential

ideas of geometry in a new context just makes it more fun.

(To create

the images, I used Gwyneth Whieldon’s setdeck package at http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/graphics/pgf/contrib/setdeck. She

also writes about it at https://whieldon.wordpress.com/2013/08/08/game-of-set/.)

Glenn

Waddell Jr. is a Master Teacher for NevadaTeach, a UTeach replication program

at the University of Nevada–Reno. He is also currently a doctoral student at

UNR, looking forward to comps and dissertation proposals in the next year. He

previously taught algebra 1, 2, and 3 for nine years in Washoe County School

District and has been an active participant in the MTBoS since 2011. He blogs at http://blog.mrwaddell.net and tweets at @gwaddellnvhs.