By Zachary

Champagne, posted June 5, 2017 —

Recently, I’ve been thinking about and sharing some of my

ideas on becoming a better

listener. In a profession where we are envisioned as sharers of

information, it was tough for me to swallow that I should be listening more and

talking less. However, I’ve come to believe that it’s the single most important

thing we can learn to do better as teachers.

One of the ideas I’ve been exploring is how providing less

structure can allow us to elicit more student thinking from our students’

written work. (Full disclosure: I was also recently inspired by my friend and

colleague Brian Bushart and his NCTM Ignite talk “Do Less, Get More”).

Consider this

problem that Mike Flynn

wrote for Teaching Children Mathematics (“Problem

Solvers: Problem: The Cycling Shop,” vol. 23, no. 1, August 2016, pp. 10–13):

Imagine you work at a cycling shop building unicycles,

bicycles, and tricycles for customers. One day, you receive a shipment of 8

wheels. Presuming that each cycle uses the same type and size of wheel, what

are all the combinations of cycles you can make using all 8 wheels?

This problem is rich with various entry points for students.

They can start in a variety of ways. Additionally, and perhaps more important, the

problem is also rich in the variety of structures that different students may

rely on to keep track of their work. I’ve seen students use pictures, charts,

tables, tally marks, equations, and more when they begin this problem.

But it is only when we provide students with the problem as

written above, and nothing else other than a pencil, that we can begin to see

the power of the blank page. As teachers, we easily slip into trying to be too helpful.

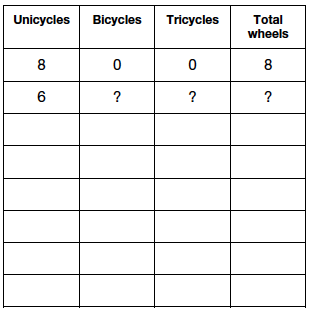

With good intentions, we take a problem like the Cycling Shop problem, and many

times we give students something like this table:

In my opinion, providing this structure before students get

started limits what we can find out about how our students are mathematizing

this situation. We are stuck with learning if they can accurately fill out a

table that we created. I think we are better suited to first let students be the problem solvers we know they can be, by

letting them solve this problem using whatever structure (if any) makes sense

to them! If students are struggling to get started or make sense of the

problem, then we can help them think of ways that they might use structure to

solve the problem. This “less is more” strategy provides us with much more

information about students and does not require them to use a structure that we

created.

I encourage you to respect the power of the blank page and

give students more space to solve

problems and less structure in the

beginning.

Zachary Champagne

is an assistant in research at the Florida Center for Research in Science,

Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (FCR-STEM) at Florida State

University. He previously taught for thirteen years as an elementary school

teacher with a specialization in math and science. During this time, he

received many state and national awards for excellence in teaching,

including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science

Teaching (PAEMST), Duval County Teacher of the Year, and Finalist for Macy’s

Florida Teacher of the Year. Zak is the current president of the Florida

Council of Teachers of Mathematics (FCTM) and is currently interested in

learning how young students think about mathematics and how to help them

understand that mathematics makes sense. He tweets at @zakchamp.

Zachary Champagne

is an assistant in research at the Florida Center for Research in Science,

Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (FCR-STEM) at Florida State

University. He previously taught for thirteen years as an elementary school

teacher with a specialization in math and science. During this time, he

received many state and national awards for excellence in teaching,

including the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science

Teaching (PAEMST), Duval County Teacher of the Year, and Finalist for Macy’s

Florida Teacher of the Year. Zak is the current president of the Florida

Council of Teachers of Mathematics (FCTM) and is currently interested in

learning how young students think about mathematics and how to help them

understand that mathematics makes sense. He tweets at @zakchamp.