By Jordan Benedict, posted September 11, 2017 —

In part 1 of this blog series, we sent out a call to change the

way we look at data: from quick snapshot vignettes to longitudinal narratives

that dig deep into your students’ individual learning story. The call to action

requires a few key shifts in how we think about using data; we want to move—

• from summative data to

formative data;

• from monitoring episodic

achievement to witnessing the complexities of long-term learning; and

• from data for accountability

measures to data used to empower students and teachers.

To see this shift in action, let's

run through steps and an example together. It’s messy; it’s not perfect; and neither

are teaching and learning. Improving the process is what makes us all enjoy our

work.

Step 1: Ask, “What do I wish I knew?”

Educators all too often do work for

the sake of doing work; we feel compelled to fix something. Instead, replace that nagging question with those

that will influence learning. The question should always align with your vision

and values, be focused on students, and feel like the answer could be

inspiring.

Step 2: Ask, “How can we measure this?”

Developing measuring tools is one of

the trickiest steps, which is likely the reason we rely on large companies to

develop testing protocols that guarantee “valid” and “reliable” results. This

insecurity has closed the door on creating agile, customized, student-centered,

data-collection techniques that inform our context. Educators should feel

liberated to create tools their teams can use. A variety of resources are available.

We used School Reform

Initiative (SRI) as a starting point. Don’t let technical jargon stop you from

creating meaningful feedback mechanisms. Make your protocols simple, use

multiple choice rubrics or scales, and prioritize uncovering the student

learning journey. Then write new and exciting chapters; language and scales can

be tweaked later.

** A step-2 side note: School personnel who have used data

for accountability rather than data for empowerment might be trepidatious to

embark on Learning Walks. Here are a couple tips to shift the focus to

learning:

• Develop focus questions that

keep the lens on students, not teachers.

• Exploit the fact that humans

regress toward the mean: A teacher doesn’t need to fear that he or she has less

collaboration time when a teammate comes in. In fact, as we collect department

data, the results will come out to a statistical average that reflects the

program as a whole, not a focus on the teacher.

• Regression toward the mean can

also protect your question reliability: For each response to a question higher

than the norm, there would likely be a response to the same question lower than

the norm. Again, the focus is to dig into the work.

Step 3: Set team norms.

Educators must feel safe with data, how the data is

collected and analyzed, and the ways the data might be shared. Data norms are a

must before teams begin.

Step 4: Collect the data in timely ways, and follow up.

Teams should have a plan for

completion and check-ins along the way. Short time frames allow for multiple

rounds of data collection. Consider limiting the data project to less than a

quarter of the year. Educators’ jobs become overwhelming at times, so it is

essential to build in guidelines and incentives for support.

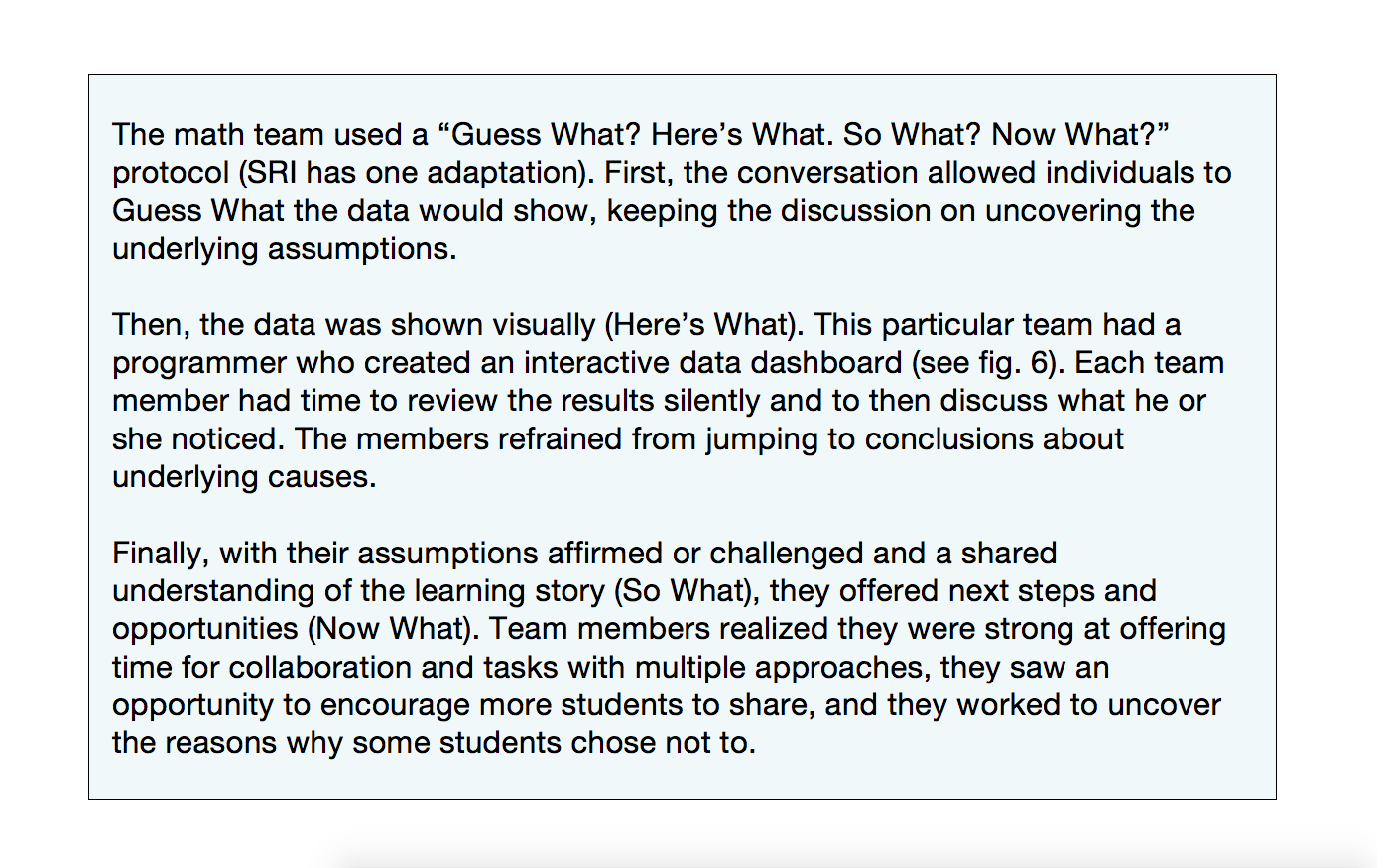

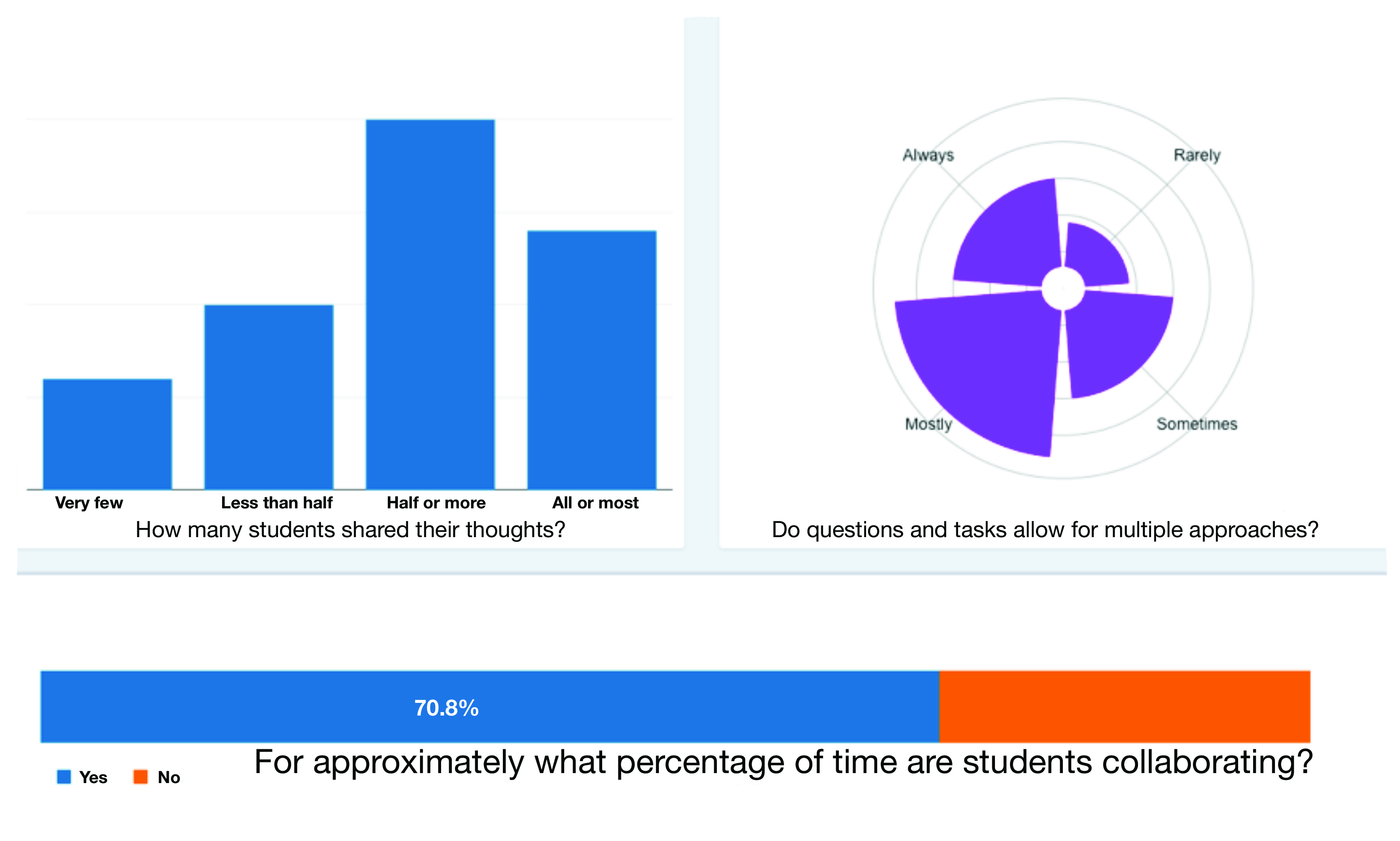

Step 5: Analyze the data using a protocol and data displays.

Our brains recognize visual patterns

from data better than they do scanning a spreadsheet. Use functions in

spreadsheet applications (.e.g., Google sheets) to make charts and data visualizations,

or use an online plot editor (e.g., Tableau, Plotly). Let your data come to

life! Adopt a protocol that focuses the conversation on results and focus

questions, rather than straying toward one particular experience. Several

resources and tools are available on my website, www.visualizeyourlearning.com.

Sample made for Shanghai American School by Jordan Benedict

of visualizeyourlearning.com

Step 6: Repeat.

This process should not be a one-off;

in research terms, we want the study to be reproducible.

The live data dashboard encourages teachers to shift, rather than moving on. If

the example team truly values students’ individual ideas, they should be

revisiting how their students progress throughout the year and watching for how

the data changes as their teaching practices shift.

Step 7: Share the data with students.

Students will glean new and different

insights from the data, and they will actively work toward the set goals when

they can see the results. Educators have a tendency to work on data and make

decisions without students, yet it is imperative that students contribute

toward their own learning goals.

The story we have told is simple: Teachers

were inspired to start a journey of discovery, they created an inclusive plan,

they ensured the safety of their team and celebrated progress, they made a

reproducible tool that tracks long term acquisition of values, and they used

the most important contributor to learning: the students.

It’s

your turn

Find your shared values, ask those

burning questions, collect your student-centered data stories, and empower

change. Use the comment section below to share your own unique data story, or

join me on Twitter @JordanGBenedict with the hashtag #EdDataStories.

Jordan Benedict

is a statistician, math teacher, triathlete, data coach, and life enthusiast.

He has spent the majority of his teaching career overseas in the Middle and Far

East, working with students from fourth grade to AP calculus. In his current

role at Shanghai American School, Benedict facilitates data workshops and

builds custom visualizations of learning data for action research projects,

department protocols, and whole school exploration. He is the curator and

creator of Visualize Your Learning,

a repository of data explorations with access to communication, advice, or

independent consulting.

Jordan Benedict

is a statistician, math teacher, triathlete, data coach, and life enthusiast.

He has spent the majority of his teaching career overseas in the Middle and Far

East, working with students from fourth grade to AP calculus. In his current

role at Shanghai American School, Benedict facilitates data workshops and

builds custom visualizations of learning data for action research projects,

department protocols, and whole school exploration. He is the curator and

creator of Visualize Your Learning,

a repository of data explorations with access to communication, advice, or

independent consulting.